This school year (2022-2023), my students and I (their English teacher) are reading together about “banned books.” We do it as part of the school’s American literature seminar. The goal of the seminar is not to thumb our noses at people who take issue with books we may like, but because such movements are important to the architecture of our lives; they shape how we see ourselves, others, and the world. We ask many questions in class about the texts and their reception by the public as we explore books that have been challenged at American schools and libraries.

We began our seminar journey in the Fall with Maus I and Maus II, graphic novels by Art Spiegelman, which illustrate his parents’ experience of the Holocaust and the aftermath of that experience. From there we moved to Feed, a dystopian novel set in the not-too-distant future, by M.T. Anderson. The story follows a group of teenage friends as they navigate a world vastly changed by advances in technology and the simultaneous demise of the planet. Then we read the graphic novel version of Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower. Butler was a prolific and much-respected African American science fiction writer, and the book is an opportunity to explore Afrofuturism. When we’re done with Butler, we’ll read The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, by Sherman Alexie.

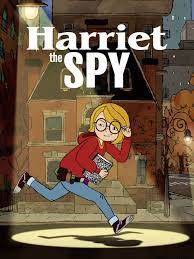

The idea of the seminar came to my mind when I learned that one of my childhood sacred texts, Harriet the Spy, has been challenged frequently in school libraries. I haven’t read that book in about 45 years, but what I remember is that Harriet was a hero to me during a time when there were not too many female heroes available in books and comics.

What has changed that made my childhood book unacceptable to people? In asking this question, I invite the students to read challenged texts closely, think about the world into which these books were born, and why they were challenged or forbidden. Students may spend some time on the fence themselves, as their own closely held ideas and beliefs are questioned, re-tooled, or rejected by the writers of our texts. Our reading helps guide us to a greater understanding of the ways in which social, economic, political, and religious movements can affect the reception of (and our perception of) a piece of art.

There is nothing new in banning books in America. In 1634, the governor of Plymouth Colony banned New English Canaan (and jailed its author, Thomas Morton) because it attacked the religious zealotry of the Pilgrims and their cruelty to the natives of the land they occupied.

Almost four hundred years later, in 2023, states across America are challenging books written for kids and young adults, arguing that kids should not have access to these materials where they go to school. In some places, public libraries are being asked to remove certain books from their shelves.

In Bucks County, Pennsylvania, a 2022 regulation now permits any parent or district resident to request a book be removed from library shelves. A new Tennessee law, passed in August 2022, allows parents, school employees, or other complainants to appeal the decisions of locally elected officials on challenged books as being “inappropriate for the age or maturity levels” of students (Rothschild).

In response to the growing trend of objecting to certain books or actively working to remove them from schools and libraries, the Brooklyn Public Library announced that teens anywhere in the country could borrow its materials (the program came to an end in July 2022).

The exploration of “banned” texts raises a basic difficulty with arguing about books from a “values” standpoint: each of us values different things. The novel I don’t want your kid to read because it doesn’t reflect my family values may well speak to the experiences and beliefs of your family. And that is fine; it is the epitome of American.

The conclusion we try to arrive at is that difficult subjects shouldn’t be avoided; if they could be, I would have gotten out of all that math that so challenged me through high school. What we shall do is try to help young people undertake subjects and tasks even though they’re difficult, even though they may fail the first few times or get tired and sore. So if new information causes discomfort, it’s a learning opportunity. Students can be engaged in discussions that explore that discomfort, allowing them to better understand themselves as well as the social debate and critical questions around them.

Importantly, challenges to books can tell us about our past (and our present)—what our culture held dear and what was considered dangerous. So we can understand why Thomas Morton’s book got him into so much trouble in 1623. And how the poor, sweet bull in The Story of Ferdinand was problematic when the book was published in 1936 because he was a pacifist in a time of war.

In seeking to understand the many issues at play, we can ask, what is our culture? How has it changed over time and through major events? How has it remained the same? Who, precisely, is being protected, and from what, exactly? Students may investigate challenges to books they read when they were younger; ratings systems applied in television, film, and gaming; or even trends in book-challenging—which subjects at which times were the most problematic? We also need to think about why Americans, people committed to free speech and the free exchange of ideas, embrace something for which the Nazis were vilified in the last century?

Works Cited